The New Testament and the Mishnah, as well as other early Christian and rabbinic writings, approached the scriptures in both similar and different manners.[i] Patient study and close familiarity with the literature often creates in readers an intuitive sense of the characteristic distinctives. Yet, expressing the apparent hermeneutical commitments of these bodies of literature sometimes tends toward unfounded generalizations. Although there is nothing particularly wrong with some generalizations, they are less than helpful if they cannot be corroborated with tangible evidence.

The aim of the present study is to offer a verifiable manner of demonstrating and measuring some of the similarities and differences between the tendencies of biblical usage by early Christian and selected early rabbinic literature with a view to gaining perspective on the New Testament’s use of scripture. In particular, comparative statistical analyses of the use of the Tanak/Torah, Nevi’im (Prophets), and Kethuvim (Writings) will reveal which writings and collections of writings were “preferred” by the New Testament, Mishnah, and other early bodies of literature. Therefore, the presentation of the graphic statistical analyses themselves is not intended to advance an argument, but to provide the kind of data from which various conclusions can be drawn. In the sections which follow the analyses I will offer selected conclusions toward which the evidence seems to point. I view these conclusions as tentative and provisional in this context apart from detailed exegetical studies.

Method

Statistics are often dangerous and easily abused. While I intend to use simple statistical analyses concerning the proportionate scripture used by various bodies of Christian and Judaic literature, I do not do so without some unease. The information for the various tables has been drawn from standard reference works. I am quite sure, though, that these at best provide a subjective, incomplete, and general picture of actual scripture use. Literary relationships are too subtle and complex to be reduced to explicit parallels and quotations. Nonetheless, I think that the statistics below generally illustrate various patterns of emphases by groups of writings.[ii] The reason for comparing Christian and Judaic literatures is to give some basis of measuring emphases.

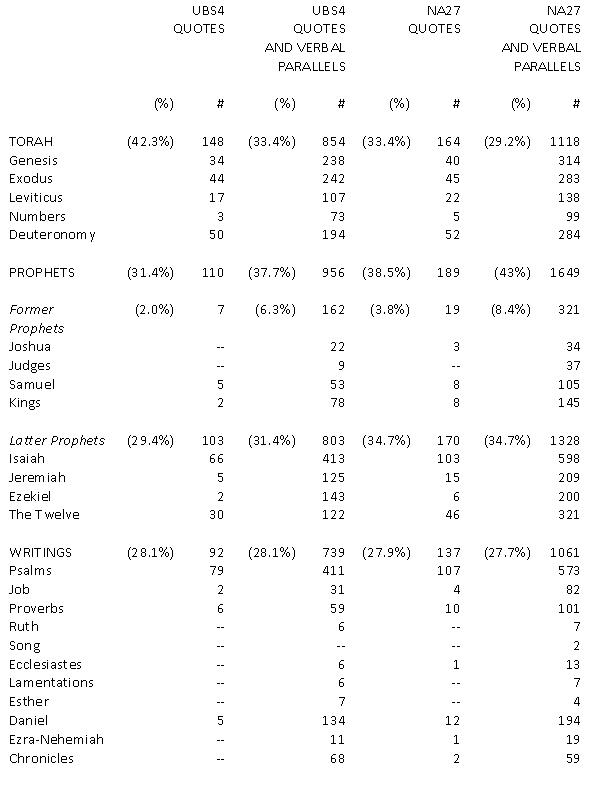

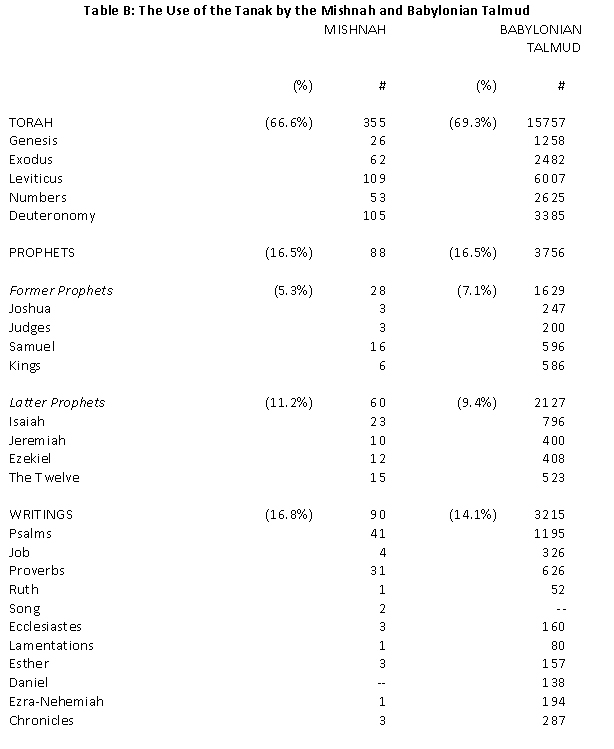

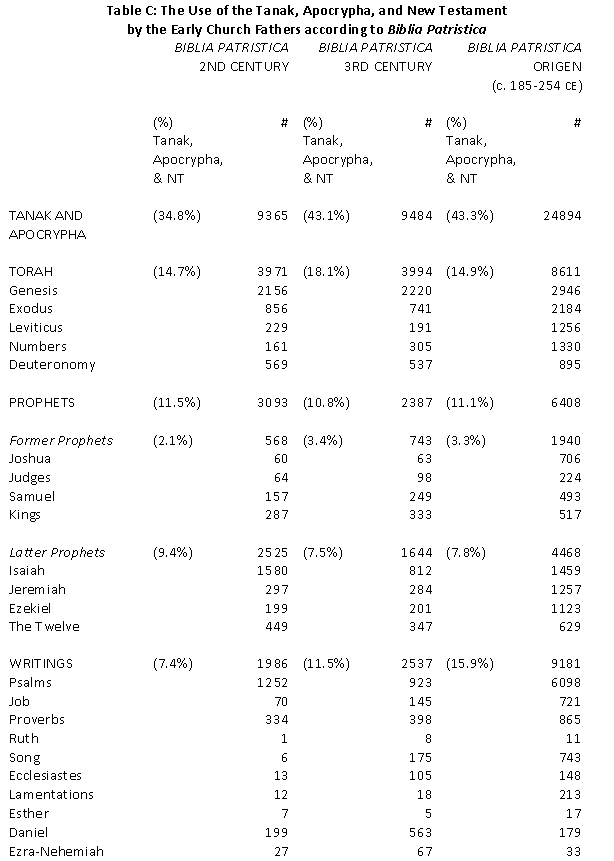

Tables A-C state the data which will serve as the basis for the variety of graphic comparative diagrams below, namely Tables D-V. Tables A-C contain quantitative information concerning the use of scripture by the New Testament, early Church Fathers, Mishnah, and Babylonian Talmud.[iii] Tables O and P will offer the information concerning the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the Pentateuch which will be applied, along with the data from Tables A-C, to graphic comparative diagrams in Tables Q-V.[iv] Tables A-N and O-V will be followed by a few of the many possible conclusions which can be drawn from this material.

Limitations and Possibilities

This study has inherent limitations and certain potential prospects. I will briefly describe two limitations. First, from among the ocean of rabbinic literature that spans from the Mishnah (c. 200 ce) to the Babylonian Talmud (c. 600 ce), I have chosen to focus only upon these two and the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions.[v] The reasons for this limitation include space and the late date of these writings in relation to the New Testament.

Second, statistical analyses do not and cannot of themselves offer a rationale as to why, for example, the New Testament emphasized certain biblical writings which were not proportionately accented in the Mishnah. The tendencies which statistics will show can complement but not replace a case by case detailed study of each scripture use.

Perhaps a few examples can illustrate the kinds of limitations intrinsic in the statistics below. One, the New Testament quotes from the Book of Leviticus seventeen times (see UBS4, 887)––that is, slightly less than five percent of all New Testament scripture quotations come from Leviticus. This “fact” is deceiving, however, since eleven of the seventeen quotes are drawn from Leviticus chapter nineteen, and more specifically, nine are from Leviticus 19:18. The general statistics do not reveal the kind of attention that the New Testament gives to Leviticus 19:18 by quoting it more than the entire rest of the Book of Leviticus. Two, of the New Testament’s 107 quotations and verbal parallels from Leviticus listed in a standard index (see UBS4, 887, 892-93), only two are identified with the Letter of James. The criteria for developing standard indices of quotations and verbal parallels is apparently unable to reflect the preponderance of Leviticus chapter nineteen allusions in the Letter of James.[vi] Three, although Isaiah 7:14 is only quoted one time and has only three allusions/verbal parallels in the New Testament (see UBS4, 888, 896), the single quotation in the first chapter of the New Testament has occupied a central role in Christian theology.

Examples of statistical limitations could be multiplied. On the other hand, if due caution is used, the relative emphases of biblical use can corroborate and/or suggest a direction for characterizing the differentness between the religious traditions that emerged from the Judaic constituencies at the turn of the era. In other words, these comparative statistical analyses will offer empirically verifiable generalizations which can be helpful if used with due caution.

Positively the statistics of relative proportionate emphases show interest and occasion. Putting the scripture use of the New Testament and Mishnah and so forth into visual diagrams produced some expected as well as some unexpected results. For example, the tendencies of the Mishnah toward law texts and the New Testament toward prophetic passages validates evident patterns within the collections. Many other familiar patterns of usage are also brought into sharp relief.

Some of the comparative analyses surprised me. Quite unexpected to me, for example, was the partially similar emergent patterns between the biblical emphases of the New Testament and proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the Pentateuch. In addition to describing this similarity, I will offer in the conclusions below an example from within the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions which, on the surface, reflects this literature’s position, in certain respects, somewhere between the Mishnah and New Testament.

Comparative Statistical Analyses concerning SCRIPTURE Use

Analyses

Table A demonstrates the subjective nature of determining exactly what constitutes quotation and/or allusion/verbal parallel. There are significant differences between the Greek New Testament indices of the United Bible Society 4th edition (UBS4) and Nestle-Aland 27th edition (NA27). For all later comparisons I have chosen to use the combined numbers from the United Bible Society’s quotation and verbal parallel indices. The reason for this decision is the frequent use of the United Bible Society’s indices within New Testament scholarship.[vii]

Table A lists the number of Tanak quotations and combined totals of quotations and allusions/verbal parallels in the New Testament according to UBS4 and NA27.[viii] The figures in parentheses are the proportions (i.e., percentages) of Tanak use relative to total Tanak use. Tables B and C will be formatted similarly.[ix]

Table A: The New Testament’s Use of the Tanak according to the

Indices in United Bible Society (4th ed.) and Nestle-Aland (27th ed.)

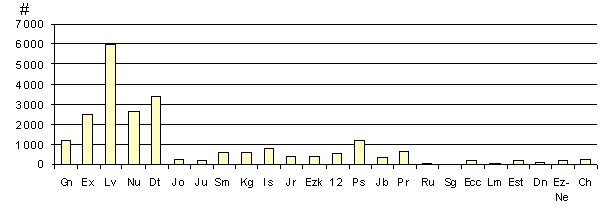

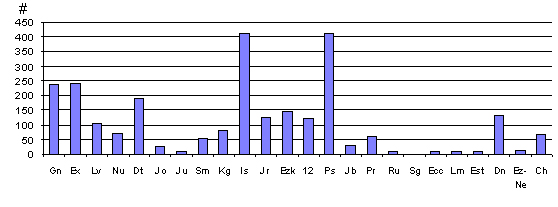

Table D: A Comparison of Tanak Use by the Mishnah

Table E: A Comparison of Tanak Use by the Babylonian Talmud

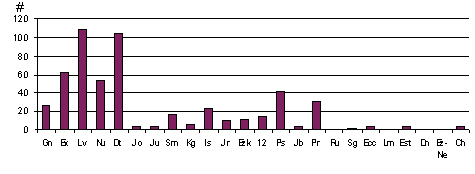

Table F: A Comparison of Tanak Use by the New Testament

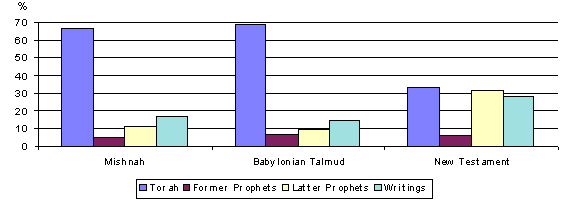

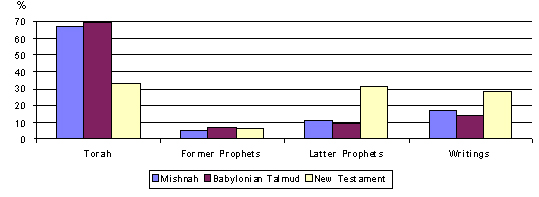

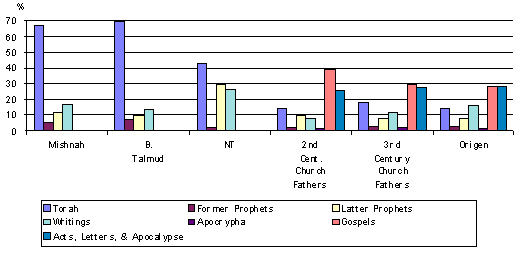

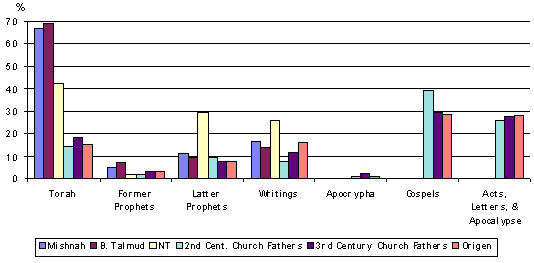

Relative to the sub-collections within the Tanak, Tables G and H offer, in different formats, proportionate comparison (i.e., percentage of Tanak use) of the Mishnah, Babylonian Talmud, and New Testament.

Table G: A Proportionate Comparison of Tanak Use by the

Table H: A Proportionate Comparison of Tanak Use by the

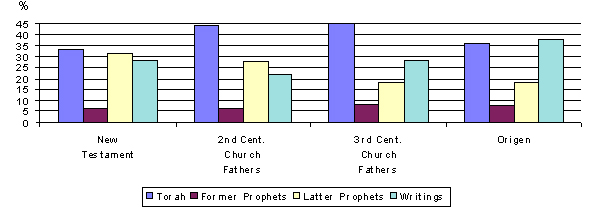

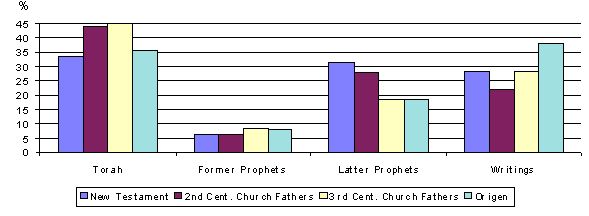

Relative to the sub-collections within the Tanak, Tables I and J offer, in different formats, proportionate comparisons (i.e., percentage of Tanak use) of the New Testament and early Church Fathers.

Table I: A Proportionate Comparison of Tanak Use by the

Table J: A Proportionate Comparison of Tanak Use by

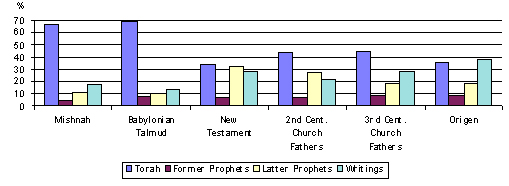

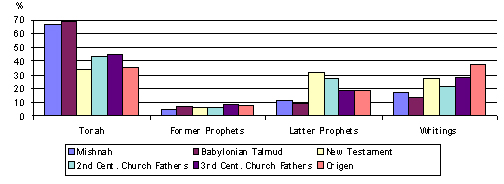

Relative to the sub-collections within the Tanak, Tables K and L offer, in different formats, proportionate comparisons (i.e., percentage of Tanak use) of the Mishnah, Babylonian Talmud, New Testament, and early Church Fathers. Tables M and N also, in different formats, compare the use of the Apocrypha and New Testament by the early Church Fathers along with the data from K and L to demonstrate its proportionate emphases in relation to use of the sub-collections within the Tanak.

Table K: A Proportionate Comparison of Tanak Use by the Mishnah,

Table L: A Proportionate Comparison of Tanak Use by the Mishnah,

Table M: A Proportionate Comparison of Tanak Use by the Mishnah, Babylonian Talmud, New

Table N: A Proportionate Comparison of Tanak Use by the Mishnah, Babylonian Talmud, New

Selected Conclusions

Tables A-N offer a number of general and uneven, yet significant insights. First, the relative proportionate use of the Tanak by the Mishnah and New Testament is more comparable in certain respects than the counterpart data from the Talmud and the early Church Fathers. Whereas the Tanak comprises the only “authoritative” writings––scripture––of the Mishnah and New Testament, for the Talmud the Mishnah functioned as Torah, and for the early Church Fathers the New Testament, especially the teachings of Jesus, increasingly functioned as scripture. In fact, for the Talmud there is a sense in which the Torah embodied in the Mishnah determined the manner in which the Talmud approached the scriptures, and especially the Five Books of Moses.[x] For the early Church Fathers, the New Testament became a lens through which to read the Tanak, or, better, the scriptures that became the Old Testament. Hence, the presence of the Mishnah for the Talmud and the New Testament for the Church Fathers must be kept in view when evaluating the comparisons. Directly related to this point is, second, that the Talmud and early Church Fathers proportionate use of the Torah, Former Prophets, Latter Prophets, and Writings, is predictably parallel to the Mishnah’s and New Testament’s use of the same, respectively (see Tables D and E, I and J).

Third, one of the few consistent things is what is not emphasized. The collections of writings assessed above give little attention in the form of quotations and allusions to the Former Prophets. Although one could say that the early Church Fathers use the Former Prophets a little more than the Apocrypha, it is probably better to note that the early Church Fathers do not emphasize either (see Tables M and N).

Fourth, the Mishnah and Talmud proportionately use the Five Books of Moses approximately twice as much as the New Testament and four times as much as the early Church Fathers (see Tables M and N). Fifth, the early Church Fathers emphasize the New Testament more than the “Old Testament.” Sixth, whether compared to overall emphases or only Tanak emphases, the New Testament is distinct in comparison to either the Mishnah and Talmud or the early Church Fathers. Or, better, the New Testament, early Christian writings, and rabbinic literature prefer different books and passages even within the same set of scriptures.[xi]

Several additional observations can be made regarding the respective Tanak emphases of the Mishnah and the New Testament in particular. This is perhaps the most useful set of observations because, as noted above, these are the only two collections of writings here treated that exclusively regard the Tanak as scripture. First, the Mishnah far and away emphasizes the Five Books of Moses most, more precisely Leviticus (see Table D).[xii] Second, outside the Pentateuch, the Mishnah most emphasizes Psalms, Proverbs, and Isaiah. Third, on the surface the New Testament appears to emphasize the Torah, Prophets, and Writings in a relatively balanced manner (see Table F). If only explicit quotations are considered the New Testament emphasizes the Torah about ten percent more than the Prophets (see Table B). Yet, if the quotations and allusions/verbal parallels are considered together, the New Testament has a nearly even interest toward the Torah and Latter Prophets (see Tables I and K). Fourth, the New Testament does not generally emphasize the Prophets or Writings, but inordinately uses the Book of Isaiah and the Psalter (see Table F).[xiii] Perhaps it is more accurate to locate the primary emphases of the New Testament with the Torah, Isaiah, and Psalms.

I would like to briefly consider the significance of this fourth observation. In specific, the New Testament has a preference for scripture interpreted. Said another

way, the New Testament tends to read the scripture as read by scripture, specifically, Deuteronomy, Isaiah, and Psalms. Considering the nature of these three books is instructive.

The Book of Deuteronomy is, in addition to other things, Torah interpreted. That is, it purports to offer Moses’ and God’s interpretation of the meaning of the previous four books of the Pentateuch. Deuteronomy is essentially cast as the three discourses of Moses. An example of the New Testament’s preference of Deuteronomy can be seen in Matthew 4:1-11. Jesus resisted the tempter by three times quoting Deuteronomy’s interpretations of the Pentateuchal stories rather than the Exodus or Numbers narratives themselves.

The Book of Isaiah, in its canonical form, appears to be a series of prophetic oracles and other preached material. More to the point, it offers judgment to the people based upon its interpretation of how the Torah was to be applied by the people. In other words, Isaiah offers an interpretation of how the Word of God (i.e., Torah) should have been applied to the life of the people. The New Testament has a dominant preference for understanding the scriptures the way they were understood in the Book of Isaiah.

Psalms is a collection of poems––songs and prayers––which reflect upon God’s world and God’s Word and poetically apply them to specific life-contexts. In short, the Psalter is, among other things, a collection of poetic interpretations of the scriptures. The New Testament’s frequent use of the Psalms demonstrates its desire to understand the scriptures as they were understood in the scriptures themselves. The New Testament, for example, often reflects upon Jesus as the promised Son of David via the Davidic Covenant found in 2 Samuel 7. Interestingly, the New Testament rarely quotes from 2 Samuel 7 in relation to Jesus (see Heb 1:1-5). Moreover, the New Testament frequently applies to Jesus Psalm 2 which poetically interprets 2 Samuel 7 and seems to read its use of “rod” (sbt) in the manner of “scepter” (sbt) in the blessing of Judah in Genesis 49:10 and the messianic oracle of Balaam in Numbers 24:17. Specifically, Psalm 2 appears to read together 2 Samuel 7 with Genesis 49 and/or Numbers 24, thus offering an interrelated poetic messianic reading of these texts. The point is that the New Testament interpreted the Davidic covenant the way Psalm 2 read it.

To summarize this point, the New Testament’s preference for scripture as interpreted by scripture––notably the New Testament’s frequent use of Deuteronomy, Isaiah, and Psalms––demonstrates that the New Testament writers believed that there was a certain way to read the scriptures. Specifically, the New Testament

read the Bible the way the Bible read the Bible.

Comparative Statistical Analyses concerning SCRIPTURE Emphases

Analyses

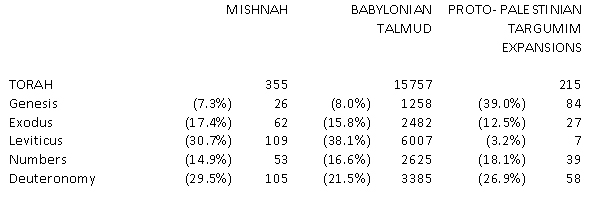

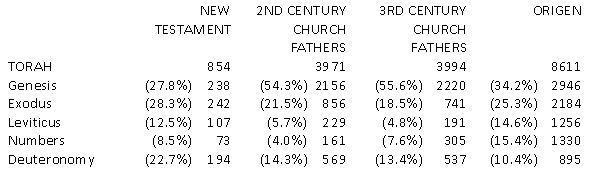

There is one other set of comparisons that I believe highlights significant differences in regard to interpretive interests, emphases, and strategies. Because the Torah of Moses was part of––but not all of––the scriptures of the Mishnah, Babylonian Talmud, New Testament, and early Church Fathers, a comparison of the relative proportionate interest toward the books within the Pentateuch is on a somewhat equal footing. Specifically, the emphasis upon Genesis versus Leviticus may in part reflect the nature of the difference between the relative interests of Christianity and Judaism respectively. In addition, it is possible to compare the emphases of the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the Pentateuch as well.

For the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the Pentateuch, it seems that the points of departure––the expanded verses––generally represent the emphases of this oral/literary tradition. For a discussion of the criteria for and a list of the expanded verses within the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the Pentateuch see the Appendix below. Again, this data is oversimplified and many other factors affect how these ancient literary traditions should be interpreted. These statistical comparisons, however, are of some value relative to demonstrating

general trends. Tables O and P will serve as the source for the data for Tables Q-V.[xiv]

Table O: A Comparison of the Uses of the Books of Moses by the Mishnah and

Table P: A Comparison of the Uses of the Books of Moses

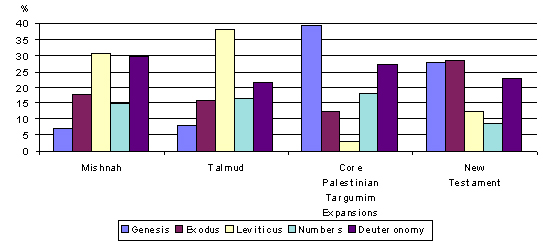

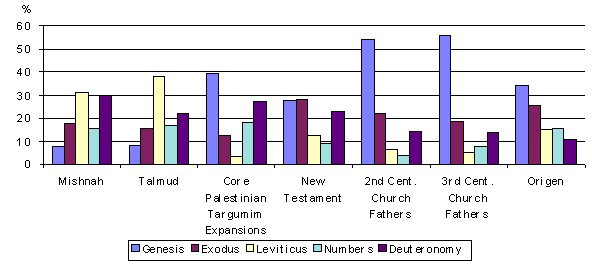

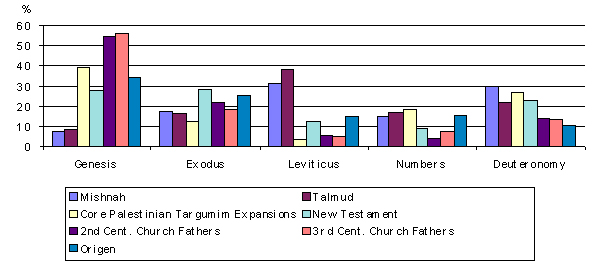

Table Q: The Use of the Pentateuch by the New Testament, Mishnah, Babylonian

Table R: The Use of the Pentateuch by the New Testament, Mishnah, Babylonian

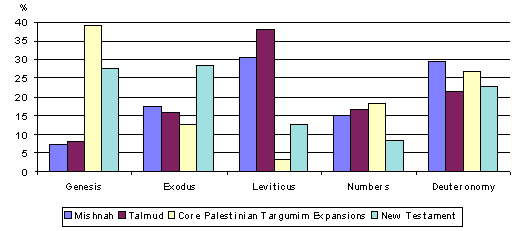

Table S: The Use of the Pentateuch by the New Testament and the Early Church Fathers

Table T: The Use of the Pentateuch by the New Testament and the Early Church Fathers

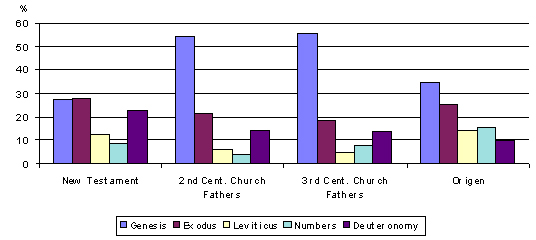

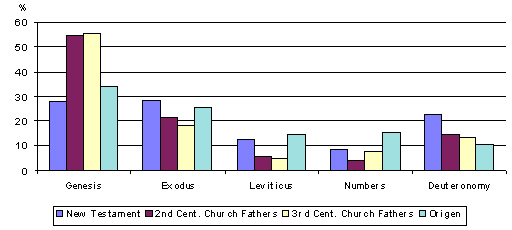

Table U: The Use of the Pentateuch by the Mishnah, Babylonian Talmud, New Testament,

For several formative collections of Judaic and Christian writings, Tables O-V illustrate in a general way the “preferences,” albeit based upon interest and/or occasion, relative to the Books within the Pentateuch. Said another way, whether the reasons are internal (interest ) or external (occasion) or more likely a combination, the respective proportionate emphasis of particular books within the Pentateuch illustrates some of the differences between the segments of Judaism and Christianity represented by their basic collections of writings.

The most notable point of contrast concerns the respective proportionate emphases on Leviticus (see Tables U and V). The Mishnah and Talmud have a statistically higher interest in Leviticus than any other portions of the Five Books of Moses. Conversely, the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions, New Testament, and early Church Fathers emphasize Leviticus the least (Origen is exceptional in that his writings emphasize Leviticus slightly more than Deuteronomy).

The next observation concerns the opposite situation regarding Genesis. Whereas Genesis is the least emphasized by the Mishnah and Talmud, it is emphasized the most by the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions and the Early Church Fathers. The New Testament emphasizes Genesis and Exodus almost equally.

A final observation regards overall patterns of Pentateuch emphasis. It seems that the collections of writings here compared can be grouped into three approaches based on Pentateuch emphases––whether by interest or/and occasion. First, the Mishnah and Talmud share a Leviticus-oriented, or perhaps better, halakhic-oriented emphasis of Pentateuch use. Second, the early Church Fathers have a common Genesis-oriented, or perhaps better, narrative-oriented and/or non-rabbinic-oriented emphasis of Pentateuch use. Third, the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions and New Testament are distinct in Pentateuchal emphases from both the approaches of the Mishnah-Talmud and the early Church Fathers. Although, somewhat different, the proto-Palestinian Targumim and New Testament each evidence similar emphases toward Genesis, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy. They emphasize Exodus and Numbers quite differently.

It seems useful to offer an illustration of the teaching from the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the Pentateuch to make this third observation more concrete. Specifically, in relation to messianic expectations the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the Pentateuch seem to stand between some rabbinic and New Testament teachings. Consider the following citations from Targum Neophiti.[xv] The italicized terms represent deviations from the Masoretic Text and the underlining is added for emphasis.

Conclusion

The statistical analyses demonstrate, at least externally and quantitatively, that the New Testament and Mishnah approached the scriptures differently. While there are some similarities, like both most “preferring” the Pentateuch, it is the differences that came into clear relief in the above comparisons. At the broadest surface level the Mishnah can be thought of as Leviticus-oriented, or, better, halakhic-oriented and the New Testament as most oriented toward Torah, Isaiah, and Psalms.

The other bodies of Christian and rabbinic literature assessed above demonstrated that the New Testament and Mishnah, respectively, set the course for approaching the Tanak. The proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the Pentateuch were exceptional in their attention to exposition of the Pentateuchal books. Specifically, in relation to emphases on particular books within the Pentateuch they appear in between the New Testament and Mishnah traditions. This possibility, along with all the scripture use tendencies measured in statistical terms, needs to be viewed as a generalization with little merit apart from careful exegetical corroboration.

Click here for Appendix on Palestinian Targumim Traditions.

[i]

Presented

at the Evangelical Theological Society meeting, November (San Francisco, Nov

2001).

[ii] See Bruce M. Metzger’s use of

proportional statistics in The Canon of

the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1987), esp. 261. Also see Donald Alfred Hagner, The Use of the Old and New Testaments in

Clement of Rome, vol. 34, Supplements

to Novum Testamentum (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1973), 338-46.

[iii] For Biblia Patristica citations and possible allusions I have consulted

Biblia Patristica, but have used the

totals from Franz Stuhlhofer, Der

Gebrauch der Bibel von Jesus bis Euseb: Eine statistische Untersuchung zur

Kanongeschichte (Wuppertal: R. Brockhaus Verlag, 1988), 40-41, 57-60. For a

positive assessment of Stuhlhofer’s work see John Barton, Holy Writings, Sacred Text: The Canon in Early Christianity

(Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997), 19, 65. Stuhlhofer’s work

is based on Biblia Patristica: Index des

Citations et Allusions Bibliques dans la Littérature Patristique, eds. J.

Allenbach, et al., 6 vols. (Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique,

1977-95); Vol. 1, Des origines à Clément

d’Alexandrie et Tertullien (1975); Vol. 2, Le troisième siècle (Origène excepté) (1977); Vol. 3, Origène, (1980). For a brief discussion

of the index strategy of Biblia

Patristica see Dwight Jeffrey Bingham, “Irenaeus’ Use of Matthew’s Gospel

in Adversus Haereses,” Ph.D.

dissertation, Dallas Theological Seminary, 1995, 15.

[iv] The appendix below, especially

Table X contained therein, defines the specific information represented in

Tables O and P concerning the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions of the

Pentateuch.

[v] For an introduction to the

varieties of Judaic literature with examples of each, see Jacob Neusner, Introduction to Rabbinic Literature,

Anchor Bible Reference Library, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday,

1994).

[vi] See Luke Timothy Johnson, “The

Use of Leviticus 19 in the Letter of James,” Journal of Biblical Literature 101 (1982): 391-401.

[vii] For example see Steve Moyise, The Old Testament in the Book of Revelation,

vol. 115, Journal for the Study of the

New Testament Supplement Series (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press,

1995), 14-16. I agree with Moyise’s qualifications––length of quotation,

significance of citation, debated nature of allusions, etc.––and concur that

using statistics should be limited to general corroboration of careful

analyses.

[viii] See UBS4, 887-901 and NA27,

770-806.

[ix] I am indebted to Luke Elliot

(research assistant) for the tedious work of compiling much of this data. The

statistics on the use of scripture by the Mishnah and Talmud are adapted from

“Index of Biblical Passages,” 807-11, in Mishnah

(Danby) and Judah J. Slotki, Index Volume

to the Soncino Talmud (London: Soncino Press, 1952), 473-620.

[x] For a case study of scripture

analysis in the Talmud see Jacob Neusner, The

Torah in the Talmud: A Taxonomy of the Uses of Scripture in the Talmud.

Tractate Qiddushin in the Talmud of Babylonia and the Talmud of the Land of

Israel, vol. 1, Bavli Qiddushin

Chapter One and vol. 2, Yerushalmi

Qiddushin Chapter One and a Comparison of the Uses of Scripture by the Two

Talmuds, South Florida Studies in the History of Judaism, nos. 69, 70

(Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press, 1993).

[xi] See Roger Brooks and John J.

Collins, “Introduction,” 2, in Roger Brooks and John J. Collins, eds., Hebrew Bible or Old Testament?: Studying the

Bible in Judaism and Christianity (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre

Dame Press, 1990). William Horbury notes the contrast between the lack of

rabbinic midrashim on the Prophets and the wealth of Christian comment on the

same (see, Jews and Christians in Contact

and Controversy [

[xii] For a discussion regarding

uneven use of scripture within the various tractates of the Mishnah see Jacob

Neusner, The Mishnah: An Introduction

(Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson, 1989), 201-203.

[xiii] It is interesting to compare the

New Testament’s use of the Tanak to the “favorite” biblical books of the

[xiv] Most of the data for Tables O

and P is adapted from Tables A-C above and the proto-Palestinian Targumim data

is taken from the Appendix below.

[xv] Targum Neofiti translations taken from Martin McNamara, Targum Neofiti 1: Genesis, vol. 1A, The Aramaic Bible, ed. Kevin Cathcart, Michael Maher, Martin McNamara (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1992); vol. 4 (1995). Also see Martin McNamara, “Early Exegesis in the Palestinian Targum (Neofiti 1) Numbers 24,” Proceedings of the Irish Biblical Association 16 (1993): 57-79. I have cited Targum Neophiti rather than one of the other witnesses to the proto-Palestinian Targumim traditions because the evidence seems to indicate that it is the earliest available, so James L. Kugel, Traditions of the Bible: A Guide to the Bible As It Was at the Start of the Common Era (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997, 1998), 943-44. Perhaps Targum Neophiti came to its present form by the latter part of the first century ce. For further discussion see discussion and notes in the appendix below.

A Comparison of the Use of the Scripture in the

Copyright © 2001 Gary Edward Schnittjer